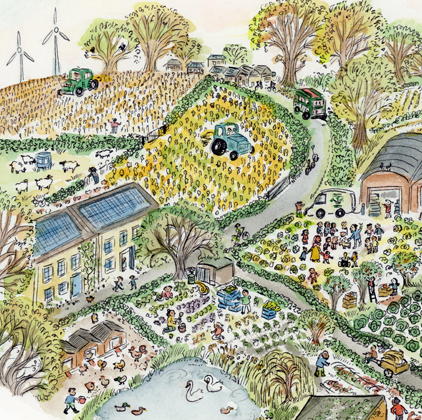

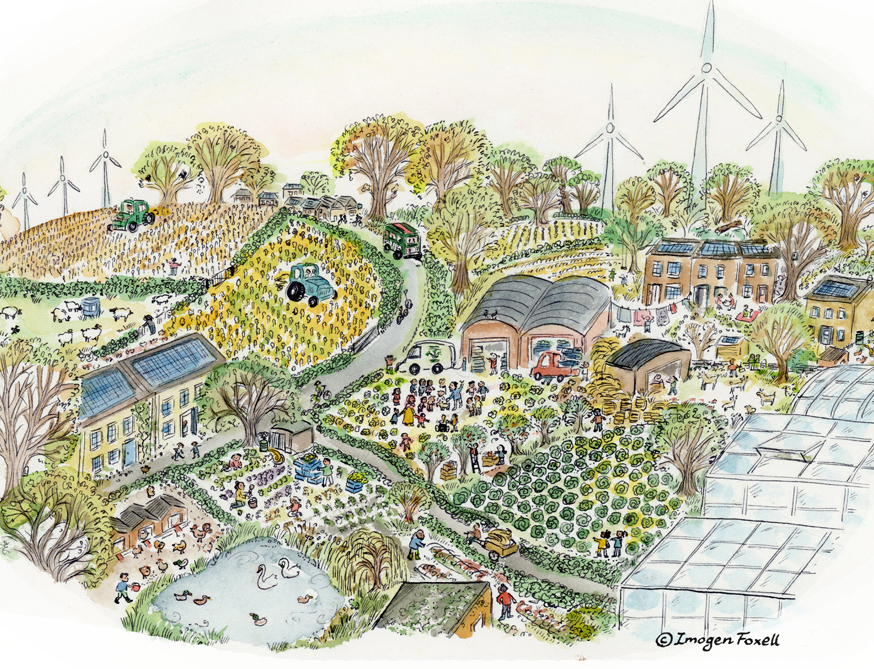

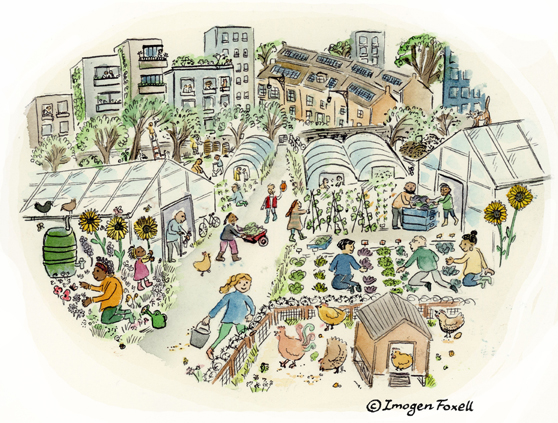

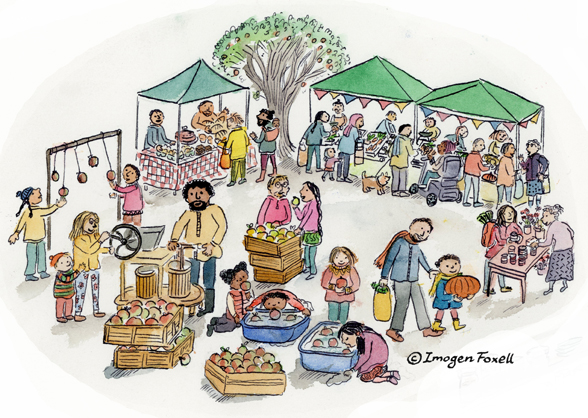

The Food Zones is GC’s vision for a better food system in the form of a diagram. The following is the vision in story form, a description of what the future might be like if we travelled in the direction the Food Zones is heading. You might recognise many of the elements as they are already in place on a small scale.

This was originally written for the GC AGM in 2015 – when it envisaged a world 20 years away. We regularly revise and update it.

Thanks to Imogen Foxell for the wonderful illustrations.

...............................................................................................................................................................

It’s 2035…

A network of farms and market gardens in and around urban areas provides at least 60% of the food needs of those towns and cities. Another 20% comes from other parts of the UK and a further 20% comes from Europe and further afield – non-perishable tropical fruit, spices, chocolate and coffee.

All regions and countries apply a similar approach. Caribbean nations have developed a taste for the occasional swede and parsnip, so ship those in as an occasional treat!

Farms are small-scale, mixed, diverse, low-input and integrated with nature to a greater or lesser degree with wild areas to attract pollinators and encourage biodiversity. Nourishment per acre has become the standard way to measure farm productivity.

Organic certification is no longer necessary as all food production is pretty much organic (although emergency use of certain pesticides and temporary use of artificial fertiliser is practised, but as the exception rather than the rule).

The key elements providing fertility for the soil – nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium – are provided by leguminous plants and animal manure. Humanure is now an established, accepted and safe way to return fertility to the soil, so composting toilets are increasingly popular. Resomation (also known as water cremation) and recomposition (based on composting) provide additional essential nutrients, meaning that at the end of life, people literally – and proudly – go back to land.

As well as being low-input, farms also generate energy – not just for their own needs but increasingly feeding back into the grid. At certain times of the year, such as during the harvest when farms’ energy needs are highest, households can top up their local farm.

How we work

At least a fifth of the population are involved in farming near where they live, and most people have a portfolio of work including some which is food-related – paid and unpaid – that enables them to live.

Farming continues to be about producing food for a living, but this increasingly includes different approaches such as part-time ‘patchwork’ urban farming, and city people involved in running orchards and farms which supply food to their communities. All children are taught how to grow food in school.

Many people are also involved in growing some of their own food at home or on allotments but more significantly they are connected to the people and the farms – be they urban or rural – that produce most of the food they eat. They regularly volunteer at their local urban market gardens, rooftop farms or underground mushroom tunnels. Those who have gardens contribute some or all of their space towards a Patchwork Farm. Everyone spends more time outdoors and has a good work/life balance.

They understand where the rest of their food comes from and how and by whom it is produced. They value and respect those people. After all, they know what skill it takes to grow food all year round, particularly as the weather is so unpredictable.

Food is valued and celebrated at Harvest festivals, potato day, apple day and the like. All commercial farmers and producers, both here and across the world, are paid a fair price for their food. This reduces the pressure on farmers to overproduce and waste. It also enables them to buy necessary skills, services and equipment on the open market.

People spend less time in the formal working economy – the official week is now three days a week – and more in the gift/shared/caring/informal economy. People still work hard but concepts of what work means have shifted; everyone still needs and wants to make a decent living but real living wages and fairer pay structures make it more possible for people to be able to do work that they feel is valuable and useful to society as a whole.

Urban areas have reduced their populations somewhat as people have moved to the surrounding countryside to produce food. That in turn has resulted in a re-invigoration of rural towns and villages, while also freeing up more urban land on which to grow more food, so that urban areas themselves are able to make a more significant contribution to providing food for their own populations. The reduced need for car parks and roads has freed up even more land for urban food production and for the creation of wild spaces that enable pollinators and other species to flourish in the city.

How we buy and sell food

Farmers sell through a range of agroecological routes to market (ARMs). In the old days, ARMs used to mean ‘alternative routes to market’ but since they now account for more trade than the outdated centralised supermarket supply chains they have replaced, the ‘alternative’ has become the mainstream. (But people had grown fond of the old ‘ARMS for Farms’ slogan and so they just changed the meaning of the ‘A’: What do we want? ‘ARMs for Farms!’ When do we want them? ‘Now!’)

Supply chain cooperation – through regional networks of traders – means suppliers’ journeys are minimised and loads are optimised. The network of Better Food Traders grew out of the Growing Communities start-up programme back in 2016 and many thousands of other box schemes, markets, shops, food hubs and online retailers have since joined the network.

Regional depots or hubs, such as the Better Food Shed, set up by Growing Communities in 2019, provide central drop-off points for producers along with other services. A very nifty bit of tech developed in 2021 ensures the distribution systems work as well as possible.

Farmers also cooperate with each other a lot more – sharing knowledge as well as larger bits of equipment and processing facilities. The Landworkers’ Alliance and the Organic Growers Alliance have expanded and now represent and campaign on behalf of thousands of farmers and growers.

People buy their fresh food from community-led ARMs, such as box schemes, markets, community shops, CSA schemes and online subscription schemes and they know how to cook and enjoy that food. Fish schemes like Soleshare – who buy sustainably caught fish direct from fishers and sell directly to customers on a membership subscription scheme – abound. So do local distillers, brewers, such as Toast Ale, and artisan bakeries like Hackney’s E5 Bakehouse and Better Health; the latter is a social enterprise which also provides jobs and a sense of community to people with mental health problems.

Supermarkets still exist but they control a much smaller share of the market and specialise in consumables and processed foods, leaving most of the fresh food to those traders better able to distribute that produce in a way that meets the needs of the farmers. The food they sell continues to come from the remaining larger more industrialised farms for whom this method of distribution still makes some sense, and they can provide some of the more basic products such as pasta and other non-perishables. But other systems enabling consumers to buy direct from wholefood coops, such as Suma, also abound, and there are plenty of bulk, unpackaged shops.

People spend a high proportion of their income on food but then again rents are capped. And people buy a lot less ‘stuff’ these days – reusing and sharing being the norm.

Changes in economic priorities and fiscal measures have meant that houses are now just homes and not vehicles for investment and speculation. The knock-on effects of that have resulted in a resurgence of housing coops and council housing. Homelessness is rare.

Meanwhile, refugees are welcomed and valued for the contribution they bring – not least their growing skills and ability to produce and cook interesting new foods. Increasing diversity in the population is leading to increasing diversity in crops and ingredients.

How we eat

People eat out a lot – communal one-pot type affairs – as it makes sense to pool resources and it’s nice to eat with your community. Not all the time though! Sometimes people splash out on more bespoke places where they can get away from their neighbours.

There are far fewer takeaways and convenience foods around; they’re just too energy intensive. People are happier to eat at home as they know how to cook and are less rushed for time as working patterns have shifted. Cooking is part of the national curriculum.

People eat a lot less meat. Any protein gap is filled by beans and pulses – from UK producer-traders like Hodmedod’s – and from urban aquaponics like GrowUp Farms and insect-based systems in the WovenNetwork. Urban chickens and goats abound – although to be honest these are used mainly for their eggs and milk and rarely end up in the pot until they are getting on a bit.

Everyone knows their fair allocation of food according to calories, optimum nutrition and environmental impact. A clever app and coding system developed in 2025 enable everyone to shop as they please while still easily keeping a tally on their ‘budget’. People can trade any spare allocation or save up for a blow-out on a luxury item.

How we live

Citizens assemblies meet regularly to review and reallocate, in the light of globally agreed climate and biodiversity targets. These need constant revision and vigilance to ensure we remain at the net zero climate emissions we achieved in 2030, thanks partly to a worldwide tree-planting programme (‘a tree planted a day keeps the climate at bay!’).

The whole economy is underpinned by a system of tradable energy quotas (TEQs) and individual carbon allowances, which enable citizens to trade goods and services, while the planet remains within the safe space required to sustain life for all species. If you cycle, walk or take public transport most of the time, you can save up for, say, a flight at a later date. You can also trade across sectors, which means that in practice it’s vegans who see the most of the world.

Economic growth driven by individual resource consumption is no longer king. A circular economy approach designs out waste and excess packaging and focuses on delivering services rather than goods to individuals. This is underpinned by fiscal measures promoting reuse, sharing, energy efficiency and payment for non-material goods and services.

So people have largely moved from individual ownership of stuff to systems that deliver shared services. As are result, hardly anyone owns a car now, but everyone has easy access to a multitude of transport options to meet their needs at any time, including shared bikes, cars, vans and an excellent public transport network. Beautiful launderettes – often combined with pubs, cafes and social centres – are abundant, while clothes libraries facilitate the clothes swapping and sharing that is now common practice.

The Brexit issue that occupied so much political discourse throughout the late 2010s turned out to be less significant as a UN/World Government emerged in 2023. It focuses on peace and sustainability. Its main task is to manage the globally agreed power-down plan in a fair and equitable way, while simultaneously enabling nation states, regions and localities to function as autonomously as they feel able to.

The whole approach is backed up by a Well Being Index, assessing human and planetary health, which has replaced GDP as the way to measure the progress of society.